Caterina Funghi and Fernando Spina

ISPRA, Bologna, Italy

The intentional taking of birds from natural populations by man can be carried out provided it is sustainable for these populations. In demographic terms, the loss of individuals from a population as a result of intentional killing or trapping should not be additive to the mortality which occurs naturally (for example through predation or disease) and which affects population size.

The demographic effect of the taking of individuals from a population by man varies in relation to numbers, sex- and age-class of the individuals taken, as well as the stage of the annual cycle when the killing or trapping takes place (e.g. during the breeding season, on post-nuptial or on pre-nuptial migration or during the winter). International legislation governing the harvesting of bird populations by man has taken these issues into account, providing measures intended to promote sustainable harvesting.

For millennia, man has killed or trapped birds for food and, in relatively more recent times, for leisure activities (sport hunting, caging). Along with cultural changes in the approach of man to nature, attitudes towards the harvesting of bird populations have changed, linked to a growing awareness of the problems affecting bird populations and of the important role that birds play as environmental indicators and in the provision of ecosystem services. The opportunity to investigate long-term changes in the attitude of man towards birds as exemplified by intentional taking from wild populations is of special interest, yet it is not easy to achieve. Thus the long historical time series provided by the EURING Data Bank (EDB) represents a unique opportunity to improve existing knowledge. We assessed the causes of changes and trends in mortality resulting from the killing of birds by man, based on geographical, historical, and seasonal analyses, as well as with reference to different methods of killing and the taxonomic groups affected.

This is of special interest given also that intentional killing, especially when illegal (i.e., breaching the above-mentioned principles of sustainable harvesting and environmental legislation), has recently been identified as a significant conservation issue. Despite most European countries aligning their national legislation to international environmental treaties, illegal activities continue to threaten European bird populations. The Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and the Berne Convention have activated specific initiatives on the topic of Illegal killing, trapping and trade of wild birds (IKB).

Fig. 1: Map of the overall dataset. For each country (centroids of coordinates/country) a pie-chart shows the frequency of intentional killing of birds (dark blue) and of birds that died as a result of other identifiable causes (e.g. killed by predator, road casualty) (green)

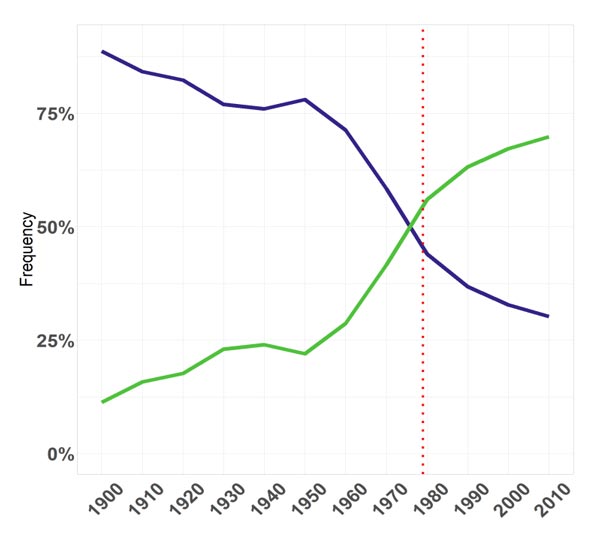

In dealing with this complex subject, we started by generating an overview of historical, geographical (Fig. 1), and taxonomic patterns, which demonstrated a declining trend in the reporting of deliberate killing of wild birds by man (Fig. 2). We considered several possible reasons for this reduction and, as a likely explanation for the observed trend, tested the role of the entry into force of the first European environmental legislation, represented by the EU Wild Birds Directive. In the different analyses performed we considered multiple spatial and temporal scales: at a large scale, we analysed how the intentional killing and taking of birds changed with the entry into force of the EU Wild Birds Directive, both for the original EU members and for those states that joined more recently. When focusing on species listed in the EU Birds Directive under Annex I (strictly protected) and Annex IIA (huntable across the EU) it was possible to demonstrate a historical decreasing trend in reporting of the former group of species. In terms of seasonal patterns, we describe different temporal dynamics across countries in reporting intentional killing birds listed in Annex IIA.

At a finer scale, we analysed the geographical distribution of “black-spots” (i.e., sites/areas of particularly intense deliberate killing of birds by man). Detecting these areas, where the likelihood of deliberate killing of birds is high, can inform conservation action to address this worrying conservation issue. Black-spot identification was performed at different spatial scales, starting with the whole Eurasian-African flyway. This is one of the first attempts to date to identify critical areas of deliberate killing of birds in Africa based on ring recoveries, to inform conservation actions on the ground. When considering protected species, the map obtained by the spatial interpolation of the data covering the period after the EU Directive showed a substantial improvement in the cells of the Mediterranean region, including the Balkans and Tunisia, while the black-spot locations in the cells covering the Middle East remained similar. In Europe, the situation generally improved after the entry into force of the EU Birds Directive. In Italy the presence of black spots persisted locally, in areas in the north and south, while a wide black-spot remained in areas of the Balkans and in Greece. Across Africa, the black-spot locations moved with time from North-Western countries towards more South-Eastern ones.

When considering huntable species, the data covering the period after the EU Directive indicate an intensification of the frequency of deliberate killing in the areas previously identified as black spots. In North Africa, black spots are identified particularly along the Mediterranean coasts and in Mauritania, with an improving situation in the Middle East, yet remaining critical across Turkey, Syria and Lebanon. During the hunting season, the frequency of reports of deliberate killing changed only in areas like the UK and Norway, which became cold-spots, while the other black-spot areas identified before the EU Directive remained and, in some cases, became wider and showed an increased intensity of killing (i.e.: Portugal, Pyrenees, Italy, Greece and Albania, Finland). A reduction in black spots was recorded across the EU during the non-hunting months.

Fig. 2: Overview of the historical trends in intentional killing (blue) and deaths from other identifiable causes (green) as percentage of cases per decade. The red dotted line and arrow highlight the entry into force of the EU Birds Directive. Data refer to all EU countries.

Finally, we exploited the unique features of the EDB to estimate the frequency of the “look-alike problem” (i.e., intentional killing of non-huntable species which are wrongly identified as legally huntable ones). Despite the limited sample size, across the EU15 countries, we recorded events involving over 90% of the protected species listed in Annex I of the EU Birds Directive which were wrongly identified as huntable species and deliberately killed, both before and after the entry into force of the Birds Directive. Deliberately killed birds of protected species are generally identified as belonging to huntable species, while a high frequency of cases of misidentification refers to pairs of huntable species.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Killing of birds by man - full report (7.54 MB) | 7.54 MB |

| Killing of birds by man - supplementary material (4.85 MB) | 4.85 MB |