Kasper Thorup and Tom Romdal (kasper.thorup@sund.ku.dk)

Copenhagen Bird Ringing Centre, Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

Monitoring changes in movement patterns is important for the conservation and management of bird populations. Such changes might affect the seasonal distributions of populations and might lead to increases or decreases in population sizes. For example, a warming climate could lead to more migrants wintering further north or moving shorter distances; land-use change could cause populations to respond to large-scale changes in feeding opportunities such as open dumps or other food resources arising from anthropogenic activities, or habitat loss. Past changes in movement patterns provide an essential source for investigating and understanding the causes of changes in migratory behaviour, thus informing the prediction of future changes. Ringing data provide a unique source of such information with the standardised method of bird ringing having been undertaken, mostly by amateurs, for more than a century.

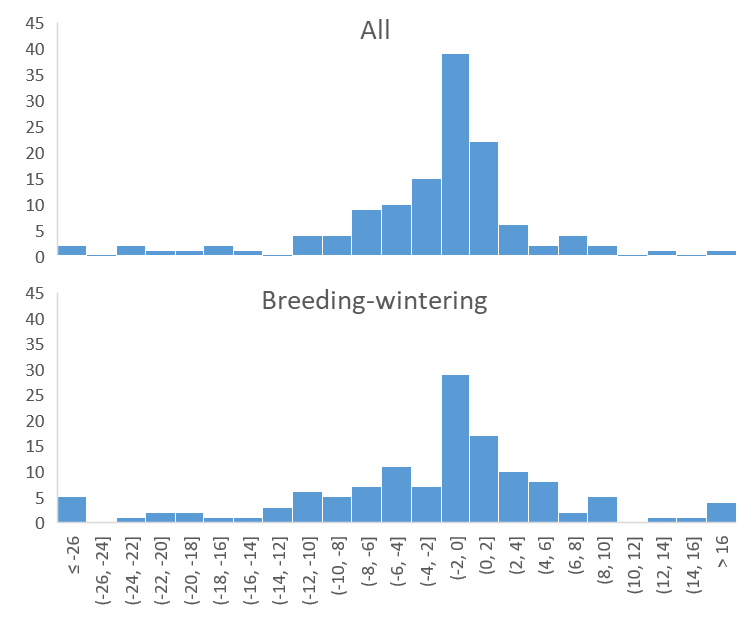

To assess historical changes in bird movements, we present ring recovery distributions for a set of 128 species with a sufficient number of recoveries (more than 50). We only present recoveries of birds found dead to avoid the spatial and temporal biases in recapture and resighting probabilities. We focus on two data sets – one of all recoveries and one of birds ringed during the breeding season and recovered during winter (breeding period defined as June-July and wintering period as December-February for all species). Identifying true changes in movement patterns from ring recovery distributions is complicated by variation in ringing effort across populations and countries as well as by spatiotemporal variation in recovery probabilities. We assess some of these potential biases by (i) separating hunted individuals from those dying of natural causes and (ii) developing two measures of correcting for biases in spatiotemporal variation in recovery probability. At a European scale, population-level changes might easily be masked by the merging of populations with opposing patterns of change.

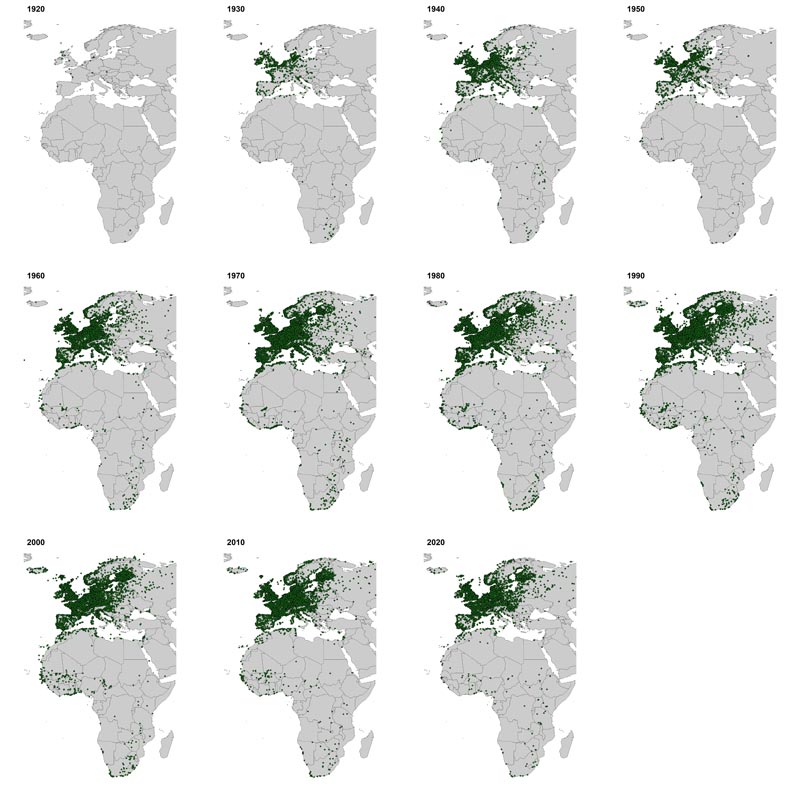

In this work, we provide descriptive statistics of recovery distributions per decade and species: Decadal maps (summarised in Fig. 1) and changes over time in movement parameters, such as latitude/longitude of ringing and recovery, movement distance (distance between ringing and recovery locations; Fig. 2) and sedentariness (proportion found within 100 kilometres), as well as changes over time in the proportion of recovered birds killed by hunters.

The majority of species showed no significant changes. Overall, there were only small changes over time in ringing locations and recovery longitudes whereas latitudes of recovery on average changed to the north. There were more species in which individuals moved shorter distances over time than species where individuals moved longer distances. In almost a third of species, more individuals had become sedentary.

Consistent changes in movement patterns were observed in relatively few species. Movement distances in white storks Ciconia ciconia decreased steadily (74 km y-1) and the winter distribution changed from South and East Africa to a larger proportion wintering in the Iberian Peninsula and West Africa. Many waterfowl showed a reduction in average migration distance but winter distributions did not change accordingly. For example, in greylag geese Anser anser we found a large change in both migration and sedentariness. Among raptors, sedentariness increased in many species but the changes were co-occurring with a change in the proportion of individuals recovered due to hunting and might not reflect true changes, as was also the case for the more southerly recovery distribution over time of marsh harriers Circus aeruginosus.

Inference at the European level is complicated not only because changes are additionally masked by decoupled changes among populations but also by changes in ringing effort amongst populations and between countries. Thus, more work is needed to corroborate our findings at the species- and population-specific levels. The results show that migration patterns are changing and provide a basis for future research relating changes in migration patterns to climate and land-use change.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Historical Changes - Full Report (818.37 KB) | 818.37 KB |

| Historical Changes - Appendix (3.31 MB) | 3.31 MB |